Alison Jefferis is a previous Executive Director and Head of Corporate Affairs at Columbia Threadneedle Investments and a current Clean Break Trustee. As Chair of our Development Committee, in 2020 she supported us to establish our corporate training programme, Achieving Greater Impact. Here, she discusses the unique insights Clean Break has to offer women working in corporate and business environments.

When I joined the board of Clean Break in 2019, my motivation was to contribute to an organisation supporting women with lived experience of the criminal justice system to transform their lives. Established in 1979, Clean Break is a ground-breaking theatre company that has been at the forefront of this work for over 40 years, enabling women to build their confidence and skills through theatre-based training, personal development, and well-being support. I was interested in criminal justice and wanted to learn more, and was attracted to the idea of a theatre company using creative writing and performance for social justice. Being somewhat outside my comfort zone added to the appeal.

What I didn’t expect, was to discover a new way of working that would enable me to become a more effective colleague, manager and leader, and would better equip me to navigate many of the challenges we face today as the corporate world responds to shifting expectations – from colleagues, customers, regulators, investors and society more broadly.

"Clean Break’s experience working with women to own and articulate their strengths, navigate blockages and build presence and influence felt like it had a lot to offer women working in a sector that has struggled to address gender imbalance."

Core to the success of what Clean Break does, is how it operates. From its co-leadership model to the myriad ways it ensures its Members (the women it supports) have a voice in every aspect of the organisation, it questions accepted practice, embraces genuine collaboration, draws heavily on emotional intelligence and creates an environment that empowers all to contribute effectively.

As I got to know and understand Clean Break, I discovered it to be an exceptional organisation working in complex terrain, and it struck me there was a lot we in the City could learn. Clean Break’s experience working with women to own and articulate their strengths, navigate blockages and build presence and influence felt like it had a lot to offer women working in a sector that has struggled to address gender imbalance. In a professional climate that is increasingly reliant on emotional intelligence to promote genuine inclusion, safeguard mental health, manage hybrid-working and navigate ongoing disruption across the workforce, Clean Break is unlike any other organisation in its ability to offer insights that are highly valuable.

After exploring the potential for a corporate training programme, in 2020 a pilot was developed with the generous support of Columbia Threadneedle Investments. Achieving Greater Impact, a one-day training session for women in business, was launched soon after. Designed specifically for women working in environments that are traditionally more male-oriented, the full-day session draws on Clean Break’s specialist knowledge and unique practice and is for women who want to strengthen their voice, create a greater impact at work and progress within their team and in their career. Each participant also has the opportunity to follow up with a bespoke one-to-one coaching session focusing on individual goals and aspirations and ways to achieve them.

"In a professional climate that is increasingly reliant on emotional intelligence to promote genuine inclusion, safeguard mental health, manage hybrid-working and navigate ongoing disruption across the workforce, Clean Break is unlike any other organisation in its ability to offer insights that are highly valuable."

Through 2021 Columbia Threadneedle’s women’s network sponsored the programme, offering the session to all female employees at junior and mid-levels. The initiative was part of a broader strategy to strengthen the firm’s pipeline of diverse leaders by supporting female talent in new ways. More than 40 women completed the one-day programme over 18 months, with exceptionally strong feedback. Many of the women cited the unique value of Clean Break’s practice along with the importance of providing a safe, creative space to explore common experiences and overcome shared challenges.

Achieving Greater Impact will enable you to focus on identifying your unique capabilities, by utilising creative tools to explore and amplify the skills and qualities you bring to your workplace.

You’ll build your confidence, becoming comfortable with expressing and owning your strengths, receiving peer support and feedback, and developing your presentation skills.

And you’ll learn how to address barriers, overcome self-limiting beliefs and workplace challenges, and strengthen your voice.

You’ll share the experience with women you may not have met but have much in common with and will likely make fruitful new connections.

Alongside all of this, you’ll be supporting an organisation that transforms the lives of individual women each day while working to achieve a society where all women can realise their full potential.

On 21 March, Clean Break spent the day at Rich Mix for ‘Inspire: Sustainability in the arts and criminal justice sector’, a one-day festival and showcase of work from the ‘Inspiring Futures’ project, which is a unique partnership of leading arts organisations working in criminal justice settings, led by the National Criminal Justice Art's Alliance (NCJAA).

The artwork for A Proposal for Resisting Darkness // Carys Wright

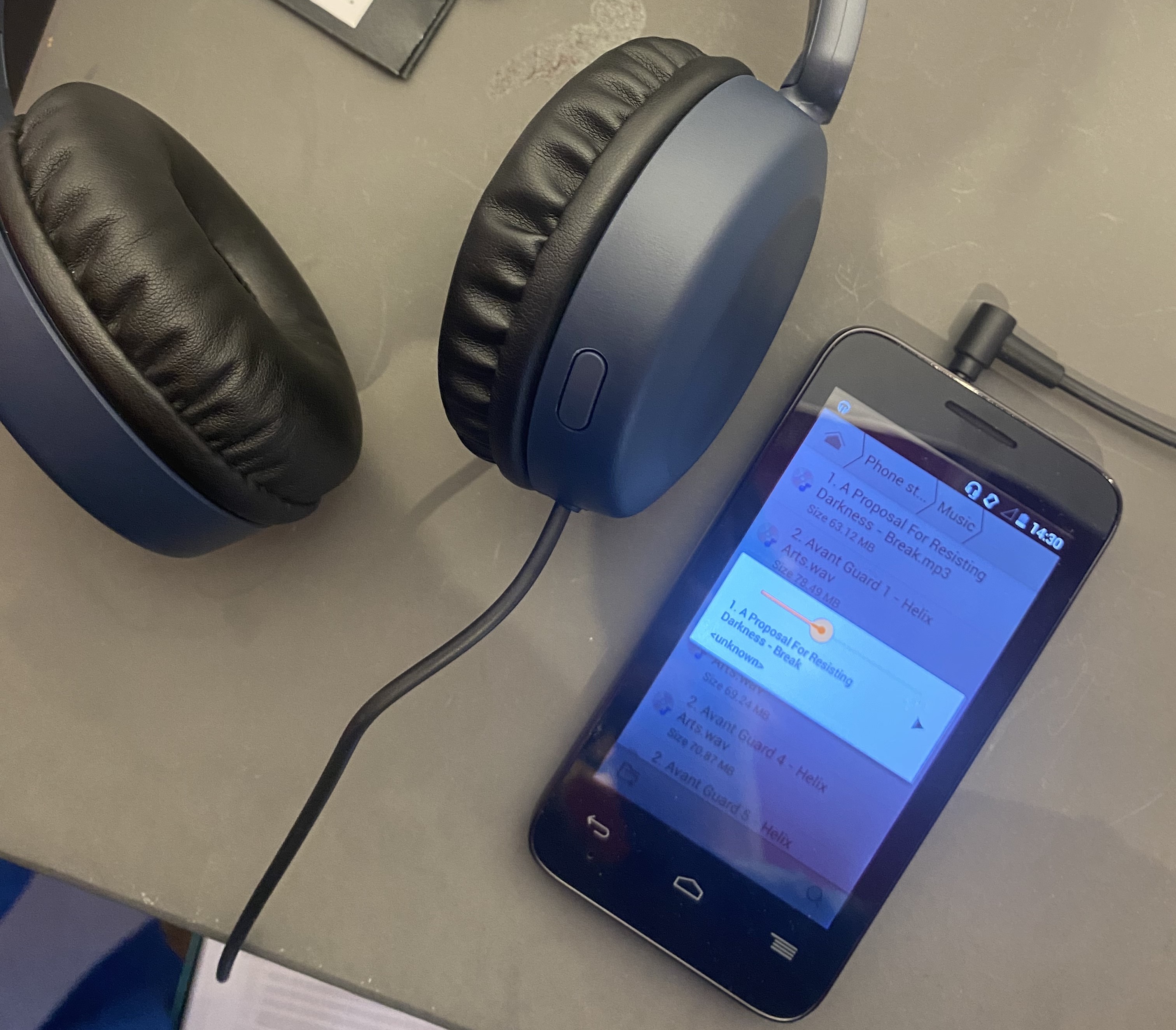

Clean Break’s participation in Inspiring Futures last year resulted in an innovative new play, A Proposal for Resisting Darkness, created by women in HMP Downview in collaboration with playwright Yasmin Joseph. Originally directed by Anna Herrmann and performed in the prison chapel, the play has now been adapted into an audio-drama and is due to be broadcast as part of a programme for National Prison Radio (NPR) this year. Hosted by NPR’s female presenters at HMP Styal, the full programme will be around an hour long, but a sneak peek of the recording has been made available to listen to at the Inspire showcase.

The day began with warm and enthusiastic welcomes from Brenda Birungi, aka Lady Unchained (NCJAA Co-Chair), Sarah Hartley (NCJAA Advisory Board Member) and Lorraine Maher (NCJAA Manager) before being passed to host Peaches to introduce each event.

First to the stage was the Irene Taylor Trust and members of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (RPO), presenting work from The Lullaby Project. This programme supported participants with experience of the criminal justice system to work with musicians from the RPO to write personal lullabies for their children, resulting in some deeply moving pieces of music. The Lullaby Project offers an opportunity for people in prison to connect with their creativity through music, and to have a space to reflect on their familial bonds, creating something that can be shared with their children. Four lullabies were performed, including a beautiful piece written and sung by Clean Break Member Michaela.

Image credit: Clinks

We had the chance to watch a powerful episode of Open Clasp’s filmed theatre piece Sugar, originally available on BBC iPlayer, which explores the realities of women’s lives lived in and around the criminal justice system. After the screening, we heard a panel discussion on digital sustainability featuring Clean Break Producer Maya Ellis and Open Clasp Senior Producer Carly McConnell, alongside Dr Sarah Doxat-Pratt from the University of Cambridge’s research team. It was valuable to hear varied and insightful thoughts around the successes and challenges of using digital media to connect with participants and increase the impact of theatrical work. Later in the day, Maya also delivered a workshop for attendees on using theatre in criminal justice settings with writer Yasmin Joseph.

Throughout the day there were opportunities to visit the installation of pieces developed during the project, which included audio recordings of spoken word, music and theatre, including our play A Proposal for Resisting Darkness. The showcase is open to the public until Sunday 26 March, so please do visit and experience the incredible work which has been produced during the Inspiring Futures project.

The organisations involved in Inspiring Futures were selected based on the impact their work has on people in the criminal justice system, their innovation and their experience. Alongside Clean Break, the partners include Geese Theatre Company, Good Vibrations, Helix Arts, Irene Taylor Trust, Only Connect, Open Clasp and Koestler Arts.

The partnership has delivered a ground-breaking programme of artistic work in prisons, alongside embedded participative research led by a team at the University of Cambridge Institute of Criminology (IOC), to gather the robust evidence needed for a recognition of the impact of the arts in criminal justice settings.

Inspiring Futures is on display to the public at Rich Mix London from 20 March - 26 March 2023.

Lead image credit: Clinks

Anna talks about the transformative power of creativity, the damaging impact of the criminal justice system on women and the passion and commitment of those still fighting for change.

I started my journey in justice-based theatre working with young people who were experiencing homelessness and subsequently young people in schools and youth centres challenging racism. I facilitated theatre training projects and devised productions to build skills and confidence, and to bring awareness to audiences about young people’s experiences. I have always had a strong belief in the need for, and value of, women-only spaces, so when the opportunity came up twenty years ago to work with Clean Break, it was a perfect combination of my passion and interests.

At first, I became Head of Education for our theatre education programme for women with experience of the criminal justice system or who are at risk of entering it. This involved leading the growth and expansion of this programme, which at its peak, offered over thirty courses every year, providing qualifications and support in a safe, women only space, from our north London studios. A key achievement was developing strong partnerships with universities where women were offered bursaries and places on undergraduate courses following their time at Clean Break, relationships which continue in the present day, providing a much-needed pathway to new skills. The role also involved bringing Clean Break plays into prisons, enabling women to engage with our work and running theatre-based workshops.

In 2018 I moved into the role of Joint Artistic Director and Joint Chief Executive as we moved into a new phase, with a commitment to ensure women with lived experience are at the heart of the company and at the centre of the theatre we create, shifting the power of who makes and tells our stories.

Over the last twenty years, I have seen how damaging an environment the prison system is for women, and how impossible it is to create a rehabilitative culture within it. I can’t see where else we have such a deeply discriminatory system at the heart of our society, which we continue to invest heavily in. I think prison shows a failure in our imagination. There is something truly incongruous about holding people in such a punitive space, while wanting people to learn, grow and make change for themselves and their families.

I’ve also seen how much the criminal justice system is an expression of patriarchy, which discriminates against women, as it’s a system designed by men for men. There are 12 women’s prisons in England (and none in Wales), with women being held on average 60 miles from home, which impacts adversely on visits from family and severs ties to community. This adds to the already devastating impact prison has on women’s mental health, with over 7 in 10 women in prison experiencing mental ill health and record numbers of incidents of self-harm reported recently.

More positively though, there is a huge amount of passion, commitment and determination in those who fight for prison reform or abolition. I have met amazing people, particularly women who campaign in this field, and that includes here at Clean Break; colleagues, artists, Trustees and Members. There is hope in these amazing people and organisations who don’t take the pressure off, and this energises me.

And theatre continues to be the transformative pillar of the work I do. Making theatre offers imaginative escape, healing and community. It helps to process difficult emotions, feel a sense of pride, feel seen, valued and recognised.

Through working with Clean Break, I have seen first-hand the impact writing and performing has on women with experience of the criminal justice system, or who are at risk of entering it. Writing allows people to tell not just their own story, but to create a world which they have within them. The women we work with often talk about finding or honing their voice through our programmes.

For women who are marginalised and have experience of stigma and negative labels, participating in a creative process can be very freeing: it’s your imagination and its valid. At Clean Break women can be free to express themselves, without labels or explanations. We all contribute to making it a respectful space to embrace a new identity as an artist, writer or performer. Our plays aren’t usually rooted in autobiography, although we are beginning this work now, ensuring we hold women's wellbeing safely within the process. Even without it being their own story, performing demands a huge amount of courage and of self-belief, to stand in front of an audience. Performing builds confidence, skills and improves health and wellbeing. If prisons took their responsibilities of rehabilitation seriously, they would invest in and nurture creativity within the walls and beyond prisons, through the gates. Creativity, arts and culture are a way for people to reconnect with their communities and contribute to society in different ways. It also allows people to not just be seen through the lens of the criminal justice system. Over the decades I’ve seen hundreds of women who haven't believed in their potential, because of damaging layers of oppression. But through creativity, with time and support from Clean Break staff and peers, they start to see themselves differently. It’s an incredible journey to witness women going on, and very humbling. A big part of our approach at Clean Break is rooted in the knowledge that people’s journeys are not straight forward. Change happens step by step, and there are so many ongoing challenges – trauma, recovery, poverty, discrimination. There's a complexity of women’s lives that we respond to, the door remains open.

The life skills women gain through our programmes support women moving on to careers not just in the arts, but in a range of other fields, for example, substance misuse services, activating their lived experience. Many people have taken that journey though Clean Break. The role of those with lived experience in changing systems for the better is now strongly recognised, a shift of discourse from the margins to the centre, which has taken place – which I hope will lead us to meaningful change.

Since I began working with Clean Break 20 years ago, some of the battles are the same. Access to prisons remain a challenge for us, which keeps arts and culture unavailable to people inside. Some prison Governors champion arts, but it is very dependent on personnel – and not considered an essential part of provision. The current funding model, the ‘Dynamic Purchasing Framework’, does not feel very dynamic or appropriate for small arts organisations – it is a deeply transactional process which has removed the ethos of working in partnership with prisons. Artists are often expected to carry keys and take on the role of prison officer (this is something we won’t do at Clean Break). Having said that, at a policy level there is an increased recognition of the value of arts in criminal justice settings, and other places where people are denied access to the arts. Recently we have seen much more buy in from some Government bodies, and the Arts Council which supports the National Criminal Justice Arts Alliance through multi-year funding.

The biggest upheaval for our work in prisons though has been as a result of the pandemic, which overnight removed access to prisons and those inside them for arts organisations. We have risen to the challenge of finding new ways to connect with people in prison, but the regularity of arts organisations having access to prisons has been broken, so we need to rebuild this.

There is positive change, however, with the women’s centre model offering a viable alternative to prisons. With women’s centres, women remain in the community and are provided with trauma informed support, by women for women. The centres understand women’s complex needs, and work without judgement to support them. This didn’t exist on a national scale before the Corston Report. We are now galvanising the public and urging the Government to provide sustainable support for women’s centres, so we are not reliant on prisons and find different ways of transforming lives.

20 years feels like a long time to have stayed in one place, but the day-to-day rewards and challenges are immense – and the drive for change, justice and equality only strengthens. It has been a huge privilege to be part of an inspiring community of women, and to contribute to change. It has given my life a meaning and purpose which I never imagined but which I am hugely grateful for.

As part of our Black History Month celebrations, we invited actor Suzette Llewelyn to speak with Esme Allman, Clean Break's Participation Associate.

The result was a wonderful conversation, covering topics from Suzette's performance in our founder Jackie Holborough's play Garden Girls, to finding community with other Black creatives and Suzette's new book: Still Breathing: 100 Black Voices on Racism--100 Ways to Change the Narrative.

Watch the full interview here:

Tracey Anderson has been part of Clean Break since 2006, bringing her wealth of experience, passion and joy to our Participation team. To celebrate this Black History Month, she sat down with Esme Allman to speak about her journey, her practice and what makes her proud to be Black.

--

Hello Tracey! First I’d like to ask you, what was your journey to Clean Break?

My journey to Clean Break was as a performer. I was at Rose Bruford College of Speech and Drama and I did the Community Theatre course. At the time I wasn't allowed to do the Acting course, that was for the sylphlike white group, and the Community course was the diverse group. I found it interesting but I can't say I learned everything there. I think I mainly learned my craft after I left but it was good, and I met good people including Cheryl Fergison, she was on EastEnders. We were all in the same college, sticking together, working together.

Then I joined the Black Mime Theatre Company with Denise Wong, she was absolutely my greatest teacher. She taught us what performing was really about, because when you’re doing mime you have to create that world, you have to create the emotions. We worked a lot with emotions as a universal language, and we brought who we were. We created, we worked hard, Denise really was brilliant. I was there for a good couple of years, in the women’s troupe first. The first show we did was called Drowning, which was about women and alcohol. It was just beautiful, beautiful work.

I then did an MA in Theatre Development. I went to Tanzania for three months working with street children, and again I used theatre as a communication tool. Being dyslexic, I didn't even know I was at the time, but being creative and practical, that was my way forward.

After my MA I started to work with the police in Community and Race Relations. That was eye opening and fascinating work. Each time I did something I found a different layer of myself unfolding. It was just amazing work, looking at racism and exploring what race is. I was looking at the ways police were miscommunicating what people do. We would talk about the ‘gaze’ and ‘defence’. I don't know if it’s the same for all Black people, but I know when I was younger if I was talking to anybody in authority, I wouldn’t look at them in the eye. I’d avert my eyes as a mark of respect, because if I looked at my mum in the eye she’d say “you think you're big like me that you can look me in the eye?” But a lot of the police officers, who were white, would think “if you don't look me in the eye, then what are you hiding?” So of course, when they stopped Black people who didn’t look them in the eye, they were looking at them and thinking “You’re looking shifty.” But the Black person would think “I'm looking down, I’m giving you respect, even if I don’t want to that’s what I’m doing.” So you can see these mismatches and miscommunications, because of different cultural experiences.

I was working with the police for about 10 years on and off, and with the Crime Academy on hate crime, I loved it. Working with the police paid for me to train and become a Craniosacral Therapist, which is another way of understanding how the body works and how we process trauma, our lives, racism, it’s very holistic.

Then in 2006 I came to Clean Break, which is about drama, it’s working with women, with trauma. But I won't lie to you the job I came to do at Clean Break, I didn't get, so I thought “I’ll go and work at the post office”, but I didn't get that job either! But Clean Break then called me back and asked if I would teach on the Access Course. I was ready to say no, but then Imogen Ashby twisted me around her little finger, and I said yes. I was having to first teach myself what I was going to teach them, about History of Theatre. But because I had to learn it first, I taught it in such an accessible way, because I had to translate how I was learning it to the Members.

From there I applied to be the Education Manager. I loved that job, we did short courses at the time, lots of courses, different aspects of theatre. One of them we did was make-up for theatre. We always used to do it in the darker months, because you’d be working with colour it was a really uplifting thing. It was also very scary though because Members would have to come in without makeup, so you’d have to be stripped bare. You’d also have to touch, which for some people is a very delicate thing. To work close up looking into each other's eyes, we had to lay the foundation and let Members know what the course was about. It wasn’t just make-up, it was a lot deeper, it was a very rich course.

Then I adopted my son so I had to take time out, and I came back under the tutelage (if you’ve seen Typical Girls, you know that word) of Jacqueline [Head of Participation], as the Members Support Manager.

I want to ask you more about your personal practise. You spoke about how theatre and performance are a useful tool for effective communication. How do your different creative mediums interact with each other, and what does that mean for your practise, especially your photography (- which is stunning and is displayed in the Clean Break building)?

My uncle was a photographer, and I don’t think I realised that I was picking it up from him, he had a darkroom in the garden. There are many Black families here who have black and white photos of their weddings, and they’ll have the stamp of my uncle on there. It's amazing, I didn't even realise.

I think it’s because of how I process things visually, I can't draw, but I can see you, I can feel you. That moment represented is through my eyes, so I'm showing you the world how I see you, through my eyes. In terms of Clean Break when I photograph Members, I want to show them how I see them, I want to show them the growth that I see. I want to show them that they’re participating. Even if you don't want to see your face, I can show you a representation that you were there, so that you know. Even if it’s just your hand, your tattoo, your elbow whatever, so you can know “I don’t have to show my face, but I was there.” It’s about showing you as who you are through my eyes, and I hope that’s done with care and with empathy and respect.

Photography came up even more because of my son. He's adopted and I couldn’t show his face all the time when he was growing up, so I use different ways to explore that. What I want to do is share those moments that I see, and that's the beauty, that's what I want to be reflected back, the beauty of life to you or to myself.

That’s what photography is to me, and theatre, it’s the same thing! It's communication, it's how we share who we are, the good and the not so good. It's just out there and you're in the story, you can see it, or you can feel it, hear it. I’m obsessed with Typical Girls, and who would think that I would like punk music! But you know what, when you get the story and the song together, come on now!

I was the same way, I've had to be schooled on punk. It’s rebel music and a lot of Black people were punk pioneers, but unfortunately they don’t get represented. I was listening to our Member artists, Eddy Queens and Lucy Edkins play and sing and I felt really invigorated!

I’m singing the tunes in my head now! That song Instant Hit, wow the harmonies in there! You know whether it’s gospel music, whatever, once there’s a harmony in there I’ve gone, I've gone somewhere. That drum, once it beats, I've gone somewhere. Whether it’s tribal, it’s deep when I hear those sounds, I'm taken somewhere else. Yeah, music is very important as well. All the arts!

We jokingly say you’re our resident DJ but since I've been here, we've been online, and the music you serve has been such an important part of celebrating our work at the end of the Season. It shows how we work with care and with joy. That brings me on to what I want to ask you about next. What is the importance of having a trauma-informed approach when you're working creatively?

We all have lived experience of something at whatever level, and for me, my lived experience of trauma is how I can resonate with the Members and with staff. Because who knows what people are holding, the more we can support Clean Break to be safe, the more the job unfolds in a different way. You’re setting the foundation for how you progress through the organisation. Once you've established that trauma informed base, by checking and rechecking and growing and learning, moving on, reflecting then putting it back in, once you do that, the work just gets deeper and richer and it grows in a different way. I think that's what us becoming trauma informed is. Yeah, things can still escalate, but not in the same way because they've been held, you are being thought of, cared for and kept in mind.

For example I hadn’t heard from a Member, so yesterday I just sent her a postcard. I just thought, “I’m letting you know I'm thinking of you.” You’ve not answered my calls or texts, so I don't know what's going on for you, but if I send you something handwritten through the post, you know I've got you in mind. The team have got you in mind. That’s what I think trauma informed is, we've got you in mind. How can we empower you so that you can let that joy come in, because too much of our default setting is thinking “that could happen again, I’m not good enough, they’re better than me, they don’t like me” and that’s protection, don't get me wrong, we have to protect themselves, but there are other ways. Life is up and down sometimes but there’s always a way, and that’s the joy. Jacqueline has a joy that I just hold my hand up to, because some days I'm just like “woah today’s a tough day” but we just fire off each other and she dances, we dance we sing, she brings joy. She has the joy of the company. Hands up Jacqueline, that's my tutelage.

I'm talking about me, Jacqueline, but I have to tell you, Giovanna [Support Worker & Members Assistant] I'm telling you that woman is off the scale! The whole Members Support team we have right now is off the scale!

The theme of this Black History Month is ‘Proud To Be’, so I wanted to ask you what or who makes you proud to be Black.

I have to go back to family, I have to go to my parents. Because I can't envisage coming into a new country with just £5 in my pocket. Leaving all my friends and my family behind and leaving a really hot, lovely place to come to a place that's a bit grey, eating chips out of newspaper. No offence!

To start living in one room, to get rejected from jobs. My mum was telling me about how she went for this job and another woman said “nah they won’t take you, they didn’t take me.” But my mum said “I didn’t care. I didn’t walk this far!” So she went there, I don't know what charm she done but she got that job. But all the rejection, and they just kept going at it until they got their house.

They always wanted to live back in in the Caribbean, so they went back and lived there. That all takes a lot of courage, I'm indebted to my parents. I would not be here now without what they’ve done and the sacrifices and turning the other cheek for all the stuff you know, I won't even go into some of the stories they told me. To me, that’s who I am and I'm proud, and I hope I can make them proud because they've given me everything I need, to be who I am now.

I love that. My family have a similar story, so that really resonates. Indebted is such a powerful word, and I hope to make them proud too.

Family is what you make it, and family doesn't have to be blood. I have friends who are more family to me than some other people who are blood family. When I say family it's about some of them aunts, who we call aunts, but who aren’t really connected, but they’ve been around all along. Now my parents aren't here, some of them will still call, checking in. They just care, they just know. When I say family I'm talking about my immediate family, but I'm also talking about the bigger word ‘family’. You know my son, he’s my family.

My final question before we wrap up, is can you tell me a bit about the importance of joy in your work at Clean Break, in your practise and in your life?

We have a supervisor who we speak to, because sometimes it can be quite challenging, the lives of Members can be challenging, the lives that we live can be challenging. She gave this advice, she said to have hand cream. Have hand cream, because when you're rubbing it into your hands it helps you to get back in touch with who you are, it helps you to ground yourself back. To me, once you’re grounded you start see the world how it really is again, and there is joy. Even if it's raining, that sun is still shining somewhere in the world and it will come back here. Yeah, there is joy but sometimes, because we've got all these other things going on, we're not remembering, we’re not holding on. Right now I'm literally holding my hands like I’ve got hand cream on!

.png)

It's hard to remember or believe that good can happen when we've had lives that have been so sad. Clean Break is about making that clean break, it’s about saying “If I trust, if I've got the support around me, there is another way to experience life” and that is the joy, that is the other side of all the other stuff. That seed you plant is going to take time to come up, but it will flower and that's what I think about joy.

We say to Members have a shower, have a bath, let water touch you, experience the feeling, the sensations, it’s warm, it’s cosy. Get something you can smell, something you can taste, something you can feel, music you can hear. Get back to your senses and you're back in the joy. You know I've always got my nice oils and rescue pastels. We should have shares in Rescue Remedy Pastels! One of the hardest things with Covid is that we can't touch in the same way, but we can still touch with our souls. Our souls can meet, our elbows can meet.

My joy comes when I’m looking after myself. And that's what we're trying to do at Clean Break. We look after you a little bit, we give you food, we help you get in with your fares, so that you can start modelling how you can look after yourself. That’s what we’re encouraging. That's where joy comes from, because when you feel good the world is open to you.

Oh, and humour! You laugh till you cry, you cry till you laugh, it’s all a release. Maya Angelou says you should laugh as much as you cry. So if you're crying too much, know you can laugh a bit as well. It’s the same line.

Photo credit: Tracey Anderson

Our new play Typical Girls, a co-production with Sheffield Theatres, is set in a PIPEs unit of a women's prison. In the play, a group of women in the unit attend music workshops, led by a facilitator who introduces them to the music of The Slits.

The play asks if rebellion can ever be allowed within such a restricted regime, and highlights tensions with those in the outside world who do not want public money spent on more progressive practices, like music workshops. But as the character Jane says in the play, "it’s not just fun. Ok?"

So what is a PIPEs unit, and how are they different to the rest of the prison estate? Lucinda Bolger is a Clinical & Forensic Psychologist, and the National Clinical Development Lead for PIPEs. In this blog she tells us what these specialised units are and how they work.

--

Women who are in prison often face complex circumstances and are some of the most vulnerable and disadvantaged women in our society.

In terms of what the ‘data’ says:

Women are 20% more likely to be recalled to prison than men, despite being less likely to reoffend.

Guidance on Working with Women in Custody and the Community. HMPPS Dec 2018

PIPEs

What are PIPEs? PIPEs are Psychologically Informed Planned Environments, and are a key part of the ‘Offender Personality Disorder Strategy’, or OPD (NHS England & Her Majesty’s Prison & Probation Service). There are currently 29 PIPEs across England, with 20 in prisons (three which are in women’s prisons) and 9 in Approved Premises (two of which are for women).

PIPEs are designed to work to the four high level outcomes for the OPD pathway, which are;

(i) to reduce the risk of reoffending

(ii) to improve psychological wellbeing and prosocial behaviour

(iii) to improve the competence and confidence of staff and

(iv) to increase the efficiency and quality of services.

People who have been ‘assessed’ as suitable for the pathway are likely to have complex emotional needs, often linked to difficult and disruptive early lives.

What does a Psychologically Informed Planned Environment look like? This depends on where you experience it; a Preparation PIPE in a ‘high secure’ prison, is likely to feel very different to a PIPE in the community. What they all have in common however are the six core components, and their relational approach.

Some of these core components are designed to help the staff working in difficult circumstances, to do so in a thoughtful and ‘planned’ way, by which we mean when approaching another person on the unit, they are able to ‘hold in mind’ who that person is, and how/why they may be feeling/behaving the way they are. On-going staff Training and Supervision (both group and individual) are core components of the PIPE model.

Perhaps one of the more innovative components of the PIPE model are the Socially Creative sessions and linked to this their enrichment activities. It is important to understand that creativity and creative interaction have central roles in our upbringing, and that people whose childhoods were focussed on survival often missed out on these activities. There is much to be said for the significance this can have on development, and in PIPEs our emphasis is on prosocial relating – connecting, belonging, achieving, winning, losing, and joining.

Key working is also a core component. Everyone who lives on a PIPE is allocated a key worker; someone to discuss issues with both large and small. This can be a challenging but rewarding part of the PIPE, as allowing yourself to attach to another person when you have been badly let down in the past is often an unnerving thing to do.

Structured Sessions are small groups which bring together people who live on the PIPE. They usually have a ‘criminogenic’ focus, which means they help participants further explore issues which may have contributed to their offence. They will often have a psychoeducational emphasis, perhaps learning about attachment styles for example.

PIPEs operate a whole-environment approach, and that process is supported by engaging with the Enabling Environments quality processes offered by the Royal College of Psychiatrists. In Enabling Environments there is a focus on creating a positive and effective social environment where healthy relationships are key to success, and the Royal College of Psychiatrists provide a kite mark when that quality can be demonstrated.

Photo credit: Helen Murray

I am thrilled to be running the London Marathon on behalf of Clean Break. As one of the greatest sporting events in the capital it is a huge honour to have been chosen to represent the company and fundraise in support of its incredible work. I am aiming to raise £2,000 by race day on Sunday 3 October and you can support my efforts here.

.png) Pictures of me mid-run on the seven hills of Sheffield.

Pictures of me mid-run on the seven hills of Sheffield.

The training process has been very exciting because it is bookended with two shows – the first in-person production we’ve hosted for audiences since March 2020, Through This Mist, a live outdoor performance at Clean Break in July, and our first main house show since November 2019, Typical Girls which opens at the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield on 23 September, just 10 days before the marathon. This means I have been scheduling my practice runs in between rehearsals, production weeks and opening nights.

In fact, over the coming weeks I will be taking on hilly Sheffield for my short mid-week runs, as I am joining the company for rehearsals there. The first day of rehearsals was highly emotional, as the company was embraced by the warmest welcome from the team at Sheffield Theatres, before a table read of the script which instantly brought the story to life.

.png) First day of rehearsals for Typical Girls.

First day of rehearsals for Typical Girls.

I loved going for a morning 5k run on day two, the perfect time to reflect on the experiences of the day before, which also offered a distraction from some of the steepest streets in the UK. Running in a new city is a fascinating way to explore it and I was enjoying the adventure of turning onto new streets and seeing where they take me. This is a breath of fresh air, compared to my usual highly regimented approach to running, which requires precise routes, distances, paces and duration. As someone who doesn’t enjoy running in circles, I need to plan my London runs carefully, so I cover a necessary distance without needing to do loops, and it’s been very invigorating to run somewhere new, ditch the planning and just go for it!

Knowing that after my run I get to go to the Crucible and get a glimpse of the magic happening in the rehearsal room is always super exciting and definitely helps me power through the occasional surprise hill, which this city has plenty of. As the weeks progress and the rehearsal process intensifies, bringing together the acting, the live music and the captivating story of the play, so will my running, offering me new challenges to keep me sharp and get me marathon ready.

This year’s marathon is extra special because it marks 4 years since I started at Clean Break! I couldn’t have asked for a better way to celebrate this occasion, than to premiere an incredible new play and do my bit to raise funds for the company.

Can you tell us a little about what you did before Clean Break?

I’ve always been driven to work with people who are without privilege and who live in places where the resources are quite deprived. I feel the injustice and have always wanted to help those who are vulnerable and might need assistance, whether that’s been in the community or in schools.

Immediately before I came to Clean Break, I was working as the education lead for a youth offending service, trying to keep young black boys (in the main) from being excluded from school.

How did you hear about Clean Break and when did you start working with us?

I saw an advert for the role of Student Support Manager in The Guardian when I was on maternity leave and applied, but it was just too soon - my baby was still so young - so I retracted my application. However, they didn't appoint, and I got a call a few months later asking me whether I was still interested.

I did some checking and spoke to a friend who used to be head of arts and leisure at the Council and she said Clean Break was absolutely brilliant and to go for it because it was the perfect job for me…that was 17 years ago!

How did you feel when you first starting visiting prison?

What really struck me was the state of them; physically how repulsive and degrading and awful they were, the number of rats, it was disgusting and inhuman.

There’s something about seeing a woman in prison – an older woman, a pregnant women - it's just another level of everything, compassion, embarrassment for us that as a society this is what we do that, you know, feeling their shame but also seeing their joy that someone's come in, who hasn't got keys, and who's coming to talk to them, to work with them, to laugh with them.

But it was all those hurtful stories about being strip searched with male officers present, being told they have to take a shower, to have a pregnancy test, it was all those awful unimaginable things that really struck me and stayed with me irrespective of the race of the woman, it was a woman being treated like that.

When I say that, I don't want to just say that women are victims, there were real moments in those prisons where I saw joy, I saw nurturing, I saw caring, looking out for each other, I also saw a lot of resilience, a lot of togetherness, a lot of sisterhood in there. I saw moments where I thought my God, I'm in awe of you because even in this environment you have managed to create a maternal space.

Can you speak about some of the pivotal moments and reflections you have on the Criminal Justice System over the past 17 years?

I think one of the one of the biggest moments was Baroness Corston’s report in 2007 when there was a political will to show what was happening in women's prisons. She did her homework, she spoke to women in prison, and her recommendations were completely on pointe.

Another pivotal moment was the impact felt by the introduction of trauma informed work and organisational gender responsiveness by Stephanie Covington in 2014. Although representation wasn’t being addressed at the time, Stephanie also recognised that racism (in itself) is traumatic so when you think of the experience of imprisonment being traumatic, these two traumas are compounded for those women of colour who are in prison. They then have the debilitating lack of opportunity when they get out, so they carry that trauma with them throughout their journey.

There were more women’s prisons back when I started working at Clean Break, but even though we have less now, it is so stark that there are over 2,000 more women in prison. During this time, I’ve seen the decimation of the probation services, the rise in short term sentencing and the disregard for many of the recommendations from David Lammy and Baroness Corston.

Did you see systemic racism in prison?

During my visits, many Black and mixed-race women were telling me how differently they were treated. How they don't get the privileges, “I'm often being told I haven’t done that right even if I was halfway to earning it”. The privileges would be withdrawn. They would never get any of the good jobs (like gardening) which would allow them out into the fresh air. They would have their leave removed so they couldn’t see their children or wouldn’t be given release on temporary licence. These are things that were subjective to the senior officer and then backed up by the governor. It’s all about power. I met one or two people in prison I thought “you're an amazing prison officer,” and then there were many more that I literally shuddered at the thought of them having any power over anyone except themselves.

What these women were telling me was borne out by David Lammy’s Independent Review.

I don't really feel like the situation has changed at all; that's not what I'm hearing from the women who have done projects with us recently. I mean there's no more strip searches and things like that because of Baroness Corston and hopefully its more trauma informed, but we're still seeing the deaths in custody, we’re still seeing things that show there's a lot of work to be done. Prisons are not a place to make money from and once we start looking for profit from those places there will be a cost, but it will be a human cost!

Can you tell us about any of the women you have met during your time at Clean Break (and how racism affected their lives)?

I have three short stories about women who were innocent.

I was really struck when I met a young Black woman back in 2004. She was 23, had a partner – who hadn’t been living with her – but moved in when she became pregnant. Within a couple of months he had changed, no longer the man she had been romantically in love with. Despite her objections, he brought Class A drugs into her home, she couldn't do anything to stop him. Her family lived many miles away and she felt that by telling them she would be putting them at risk. The police raided the house and found the drugs. He was already in trouble and had other charges against him, so he told her that she needed to take the rap for him. He threatened her and the baby so in the end she decided to do what he said. They imprisoned her at five months pregnant, with a completely clean record, and they didn't even question as to whether the drugs could have been her partners. I asked why she thought this had happened, and she said she thought that “they were just happy to get someone.”

She had the baby in prison, and they handcuffed her all the way to the maternity ward, she was in so much pain and distress and yet still they restrained her. That baby remained on the child protection register until she was 18 even though her mother never took a drug in her life and was innocent of the crime. Her world was turned upside down, but she showed enormous strength and resilience and she is doing incredibly well and is now helping other people to turn their lives around

I met another woman in prison, she was older, in her early 50s. She had been a carer for 28 years, devoutly religious. She was part of a team caring for someone in their home when money went missing. There was no evidence that she (or any of her colleagues) had taken the money and when I asked why she thought the finger was pointed at her, she said “I can only think it's because I'm Black”. She was arrested, went to court thinking it would be thrown out, but instead got sentenced for six months.

The sum of money was £10! That floored me, it floored me! She is one of the calmest women I've ever met, she just said “I'm going to be praying, you know I'm sure they're going to find out that I didn't do it, I’m not a dishonest person I would never do that.”

She was a really positive influence on the other women in prison, praying with them, giving them recipes. She was released after two and a half months, spent some time with us at Clean Break and then moved to the Midlands where she could start again to rebuild her life and her reputation.

The third story is about a white woman who was also really young, she was doing an MA in criminology. Her boyfriend didn’t live with her, but without telling her, had stashed Class A drugs at her home because it was a safe place to hide them. He got arrested whilst out with friends and the police raided his flat, and on finding nothing, raided the home of his girlfriend. They found the drugs and questioned her, and although her boyfriend confessed that she knew nothing about them and took the full blame, they charged her, she went to court and she was sentenced to 20 months in prison.

She said the judge said to her that he “wants the full weight of the law to fall on top of her because there is no way a middle class, intelligent young woman like her should be going out with people like him, people like that.” She said the only word he didn’t say was white, she said he didn't need to. Her boyfriend was Black, he also went down, they still charged him, but it just wasn't enough they wanted her to be punished as well, to see the consequences of association.

These are just three stories, there were loads of women I talked to who said that “I'm innocent, I haven't done anything, I've been coerced!’ It's interesting to think how those cases would be looked at now, with a different pair of eyes but who would look back at these stories now and not say that that's a form of injustice?

What does Black History Month mean to you?

Black History Month (laughs) I do have to smile, I mean it's one month to celebrate good food, rich culture, fresh new ideas and I suppose it's also a chance to see many more black faces, new and old on our screens.

I look forward to hearing all the Members ‘sharings’ because there are people who have a myriad of different experiences that are connected to me. It’s an explosion of form, they are full of such rebellion and resistance they are emotive. I can feel quite sad but equally uplifted and empowered there's just more colour on the screen, things just get more colourful, noisier, vibrant and lively!

I'm joyful too because one of the biggest tools against oppression and suppression is humour and you know that's to be found in loads of places but one of the times I see it more is during Black History Month.

But then I think it's all crammed into one month! I mean we're not going to go and hibernate for 11 months, we need to be seen, we are a part of everyday that is the truth. We need to be seen and we need to be heard. I have this analogy which actually was part of a proverb someone told me and it's a bit like during the month we can sing and dance, do whatever with lots of pride and then during the other 11 months we've still got to dance but we’ve got to watch our side and what that means to me is in that month we're out there but when I say dance it means we still have to live, it’s a metaphor for living but we’ve got to watch our side we’ve got to be much more careful those other 11 months.

It’s important that people don't feel that they've been given a month to say every single thing that happens to them or what they'd like to see across the year and then are told to shut up.

What are your hopes for the future?

That’s a big question! I have so many so I’m going to break it down into a few bullet points!

And finally, I would just like to give thanks for all our wonderful powerful talented community of women, our Members, staff, artists and volunteers – and my last thoughts are for all our continued health!

Photography: All The Lights Are On, Tracey Anderson

Paulette Randell MBE is one of the most influential women in theatre and television. She has directed at many of the UK's leading theatres, was the first Black woman to direct a dramatic play on the West End, was the Artistic Director of Talawa Theatre Company and is behind many of your favourite shows on TV. Her path through the industry is also closely linked with Clean Break having met one of Clean Break's founders at drama school. For the company, she then went on to write 24% in 1991, direct one of Clean Break's seminal plays Head-rot Holiday by Sarah Daniels and was Chair of the Board of Trustees.

As part of Clean Break's Black History Month celebrations we invited Paulette to have a conversation with our Development & Members Assistant, Demi Wilson-Smith. The basis of their conversation was 24%, inspired by the percentage of Black women who made up the prison system in 1991 and focusing on the impact the criminal justice system had on young Black women. With the impact of that play as a spring board, in this interview they discuss intergenerational activism, culture, being Black women in theatre, the criminal justice system, the future for Black voices and the search for Paulette's missing play.

#FindPaulettesPlay

In our final 2 Metres Apart blog, Nicole Hall and Katherine Chandler look back over eight weeks of working together remotely.

I was excited, nervous, buzzing before our initial conversation. Having been offered a place on the project it was as though things became very real.

Although we didn’t know one another I felt an instant connection and Kath’s warmth, wit and compassionate nature put me at ease (we clicked).

The hour chat felt like 5 minutes and before I knew it, we were off the call and I was left with a mixed bag of ideas (buzzing).

Being a performer and having the freedom to do what I wanted with it without a pre written script and direction left me feeling like a little fish in a huge ocean (after flapping for a while, I allowed the flow to carry me).

The one thing I did know for sure was that we are a perfect match (thank you Clean Break)

I tried to go into the process with a complete blank page and yet the synchronicity was unreal. We both felt the magic of lockdown coupled with the comedy amidst the trials and tribulations was a great starting point.

On the second call we discussed our week and again it flowed, I felt the element of music (my first love) had to be in the mix. I’ve never written professionally but Kath made me feel at ease about it all as she referenced my emails as ‘writing’ (oh yeah. lol)

Through the struggle of life in lockdown, responsibilities and the lot there is a beauty which is hard to deny; love, compassion and a sense of freedom (when I allow it) when connected with likeminded people (such as Kath).

Third call, again things flowed there was laughter and banter etc – more of the same please!

Our last session was off of the back of me having had a tricky week. I felt a lot more solemn and could be nothing but honest about what was going on for me. Kath helped show me the positivity (she’s a real light) I felt the fear creep in with the feeling of ‘endings’ and Kath gave me a real 180-degree spin on it and suggested it was but a beginning to endless possibilities. Undeniably the experience is one to always treasure and has reignited that fire which had been dimmed (but always flickering) for a while.

Here’s to even more of the same (I hope) the next phase of 2 Meters Apart. To the whole of Clean Break, (Staff, Members and Artists) I thank you (from the bottom of my ‘cheese ball’ heart).

Over and Out x

Me and Nicole first met by phone. I was nervous about the first connection just because we didn’t know each other and I wanted us to get along. Nicole felt the same. We got along straight away. We had an hour chat. We’re both talkers. We had a laugh. Nicole is open and funny. We talked about who we are and what we are interested in creatively. Nicole has a particular interest in music and comedy and magic. Without knowing this I had already started to write a monologue about a woman stand up so I felt optimistic that there was a creative connection already bubbling.

We agreed to meet on Zoom the following week, again there were nerves - what if we ran out of things to say or something went wrong?

Again we talked for an hour. We could have talked for more. Zoom chats have become so everyday and if felt easy to communicate this way. Nicole has lots of stuff going on. We talked about lockdown, about our families, things we were dealing with. Our ‘everyday’ becomes the main topic of our chats. Our days, every days, ordinary days, extraordinary days, bad days, good days, getting through the days, Cardiff days, London days, sunny days, lost days. That feels like something to me. I don’t know what yet. I ask if in our next session Nicole minds talking through her everyday for me.

Between sessions Nicole emails me with thoughts. Sometimes things that have happened in her days. She sends me short YouTube videos of her performing magic. Flashes of who she is.

Our third session was more of the same. We still laugh and chat, I think we’re both open with lots of similarities and common ground and over the weeks we’ve got familiar with each other. Nicole makes me think about stuff. I value our hours.

The openness of the project has allowed us to take our time, see what happens, which can prompt a low level confusion for me that I’m not doing something right but slowly ideas begin to come into my thoughts.

In our last session Nicole talked about the end of the project and I suppose I hadn’t thought of it having an end. I feel like it’s a start. The thoughts, still unformed, are in my head. Stage 1. Phase 1. First wave. Pre-peak - Lockdown jargon.

Read our other 2 Metres Apart blogs:

Lucy Edkins and Sonya Hale

Funke Adeleke and Danusia Samal

In our second 2 Metres Apart blog, Funke Adeleke and Danusia Samal reflect on the process of making art in lockdown.

It has been a cathartic journey working with someone as talented as Danusia. She has been helpful, constructive and suggestive along the way. Which in turn has helped to shape the way we’ve worked.

From our first chat we talked freely about our experiences in lockdown and how we are coping.

This in turn fed into our discussion about the things we’ve missed and what we yearn to get back to once the pandemic is over.

We discussed missing live music, performing and seeing shows.

This helped to form an idea of what we would like to put into our creation. We also talked about what has been happening to us as individuals and I told Danusia about my experience of living with a new flat mate and how they are truly disrupting my life.

She helpfully suggested different ideas about how we could go about creating something by the second week. The first being a website that we could use to exhibit the work we create.

We jointly decided to call it Vibrations, as in the feelings that we’ve been going through during the lockdown, both high and low.

In the next week, I started to write different poetry which I submitted for the website.

Then Danusia, suggested that we write monologues from the perspective of the two housemates.

I wrote from the male’s perspective and she wrote from the female’s perspective.

By the fourth meeting we had both worked on the monologues, redrafting them as necessary in the previous weeks, the monologues include music and spoken word.

Currently, I am learning both monologues to record them as a video which Danusia will edit cleverly and they will be on our Vibrations website.

Working on this 2 Metres Apart project has really helped to shape the way I work and ask questions as well as think about things I wouldn’t normally think of.

It has also shown that it is quite possible to collaborate with the aid of the technology that we have available to us nowadays, so although it isn’t the ideal situation. It can work.

It has been a joy to have something to fully focus my energy on as well as material for my acting showreel which is all very exciting for the future and can’t wait to share what we’ve been working on.

Funke and me had our first virtual ‘meeting’ in mid-May – a cathartic catch-up about our lockdown experience so far and the things we missed which Covid19 had snatched away: Theatre, nights out, live events. We’re both actresses and singers. We’d both performed in bands and although the previous year had brought less music to our lives, we both missed live music, singing, and being part of an audience.

You’d think it might be depressing to talk about this, but actually it became an interesting discussion on how we could regenerate that feeling, even if it was going to be a while before we performed anything live, or saw anything live.

It was in that spirit of ‘liveness’ that we let our first couple of sessions be chats about anything. Our week so far, what was annoying us… we also talked about what could we make and how we could be creative. I then compiled a list of some ideas based on what we discussed. You can see them below:

In the end we selected and merged a few of these. We created a website which could be a space to put our ideas. Then we started writing together. The piece is two sides of an argument - inspired by stories Funke told me about where she was living (don’t worry, it’s still a fictional piece!) Funke wrote a brilliant monologue from the point of view of a male flatmate and I wrote a response from the point of view of the female.

Since then, we have gone back and forth discussing and editing our pieces each week. How do they tie together? Who are the characters talking to? What is the journey? Funke is playing two very different characters with opposing perspectives on a household dispute. She is doing this brilliantly. Poetry and music will hopefully weave their way in too.

We are now at the stage of final drafts of our monologues, which Funke will rehearse, perform, and record in the next few weeks. I’m looking forward to then editing the two pieces together – using sound and music and video editing to tell this funny, familiar, and hopefully relatable lockdown story. We have both really enjoyed 2 Metres Apart and we are looking forward to sharing what we have made.

Read our other 2 Metres Apart blogs:

Lucy Edkins and Sonya Hale

Nicole Hall and Katherine Chandler

Over 8 weeks during lockdown twelve pairs of Artists met digitally as part of Clean Break's 2 Metres Apart project. It was a space to work creatively, share ideas, and see what arose from the process whether that was to co-write together, to each respond to a selected stimulus, or for one artist to write for their partner to perform. The project was focused on practise rather than product, providing our collaborators the space to explore and experiment.

In three blogs, we have asked 6 of our Artists to reflect on the process of this new way of working, published alongside their collaborator. In our first blog, Lucy Edkins and Sonya Hale share their experience of working together and the triumphs and challenges of making work under lockdown.

Mid April

A lockdown collaboration sounded like a lifeline to me. My two foster girls have just moved back in with their aunt after a total meltdown induced by lockdown insensitivity to their case from the powers that be. My son and I, enjoying the calm after the storm, were frequenting my little studio near Markfield Park so that we could have a change of scene and get into a bit of spray painting.

In the midst of producing silly self-tapes for adverts, writing up the answers to the Clean Break questions was a welcome slice of reality. In keeping with the self-taping, I filmed the answers in the studio kitchen while my son struggled with his home schooling and people worked around me.

Early May

A month after the girls left, I get an email to say I’ve been successful – it starts almost like a rejection, saying how many high quality applications they’ve received, so I was steeled for that, but very happy to get accepted, and later was pleased to see how many familiar faces I saw on the project.

Sonya seemed as keen as I was to get the ball rolling. We were emailing the next day and by Friday I was at a street party with kids doing sponsored runs for the NHS and bunting up for VE Day. After a comedy moment trying to answer my phone, I took the call around the corner away from the noise and we got chatting. Sonya was energised and inquisitive – her method was to fire off a lot of questions, some of which I could answer there and then, some of which I hesitated to share with the neighbourhood.

So, the next step was writing. I did my best to keep up. Essentially, we bashed out the idea pretty quick. Then it was a matter of responding in different media... I was creating a body of work in spray paints, inspired by my son’s enthusiasm for the medium and our creation of a character who did the same. We began by talking up the possibility of a short film idea. I would do a lot of the filming, create ideas for visuals, perhaps do voiceovers, and Sonya would concentrate on the written structure of the piece, the plot, etc.

Sonya worked by getting responses and pulling the various fragments together, always checking in to make sure I was happy with the process.

It became apparent that a short play fitted more into the expectations of the project and what we were able to achieve in the time given. Sonya got busy and thrashed out the results of our to-ing and fro-ing and I responded with a few little edits.

I think the blend of our voices was an interesting and stimulating process, and, given more time and commitment, could produce a unique and engaging piece of work. I hope Clean Break are able to continue to support these kinds of collaborations between Members.

breathe by Lucy Edkins

breathe by Lucy EdkinsI was delighted to be asked to do the 2 Metres Apart project and even more delighted when I was partnered up with Lucy Edkins. I didn’t know Lucy but had, however, seen her perform in Inside Bitch at the Royal Court theatre and I was very impressed. When we got chatting we discovered we had many things in common; Lucy and I both have a ‘colourful’ past, we both have teenage sons and we are both interested in a variety of arts. Lucy, however, usually expresses herself through fine art while I more commonly write. Initially Lucy said she didn’t want to write but when I read some of her amazing work I knew she had to. Similarly, initially I said I didn’t want to perform. However, after discussion we both encouraged each other and embarked on a real partnership whereby we would both write and perform.

To start with we decided just to have fun creatively; we embarked on a game of artistic consequences whereby I would write or draw something and send it to Lucy who would respond by writing or drawing (or painting) something inspired by what I sent. We wrote and painted some great things. I had not painted since high school so it was an incredible experience for me. What emerged was a lot of wolves and moons and howling and also lots of references to the sea. Also, two strong characters started to emerge, namely Spray-girl and Tent-girl. Spray-girl was very much inspired by Lucy and Tent-girl was very much inspired by me. Lucy sent many images and ideas and I started to weave them together into a short story. Once we had the basic framework for the short story, we could start to shape some of the poetry that we had written in our game of consequences and chisel it into shape to fit with the tale we wanted to tell. Lucy wrote a lot of beautiful, exciting poetry so we decided to include a lot of direct address monologues in the piece. It worked really well.

Working with Lucy who is very creative but historically expresses herself in very different ways to me really encouraged a little artistic explosion whereby we both felt inspired by each other to work in different ways. I have not drawn or painted for many years and I felt very rusty when it came to this. However, our experiences like this in real life became fuel for events in the story that we wrote. In the story Tent-girl, like me, has never expressed herself artistically before and in the story we wrote, as in life, the two girls would never have met before if it hadn’t been for coronavirus but thanks to the lockdown situation they end up sharing a lot of artistic work and uniting on this.

This project, for me, felt like so much more than just a coming together to write a piece for a commission. Lucy and myself really worked as a partnership; we encouraged each other to express ourselves in new, unique and beautiful ways. We submitted the first draft of our little story and I hope that we get the opportunity to work together more in the future, to sculpt it and then perform it together. But more than that I hope Lucy and myself continue to encourage each other creatively, by continuing with our game of artistic consequences amongst other things, to see what else emerges for the future.

Read our other 2 Metres Apart blogs:

Nicole Hall and Katherine Chandler

Funke Adeleke and Danusia Samal

The Children's Society - Protecting children from being exploited by criminal groups

Inside This Box is a powerful production highlighting the harsh reality of life of young people who are coerced into criminal exploitation. It shows their vulnerability and the trauma they experience trying to deal with terrifying situations, often on their own.

Young people define child criminal exploitation as ‘when someone you trusted makes you commit crimes for their benefit’. This is the definition we use at The Children’s Society. It conveys well the key components of exploitation – a trusted person taking advantage of children’s vulnerability to deceive, control, coerce or manipulate them into criminal activity. This can include work in cannabis factories, moving drugs across the country, shoplifting, pickpocketing, or threatening violence against others.

Recently, child criminal exploitation has become strongly associated with one specific model known as ‘county lines’. This involves organised criminal networks exploiting young people and vulnerable groups to distribute drugs and money across the country through dedicated mobile phone lines, often from cities to smaller towns and coastal communities. ‘County lines’ is no longer a fringe issue, but a systemic problem reported in almost every police force in the country.

Children are being cynically exploited with the promise of money, drugs, status and affection. They’re being controlled through threats, violence and sexual abuse, leaving them traumatised and living in fear. For criminal groups, exploited children are a commodity they are prepared to sacrifice to avoid themselves being arrested by the police.

There are many signs that a child may be groomed for exploitation or is being exploited – from changes in behaviour to going missing, coming home with unexplained expensive gifts or looking anxious every time the phone beeps.

Sadly, our research report Counting Lives found that signs are too often missed or ignored and that many children remain under the radar of professionals who can help them until they are trapped in the cycle of exploitation. They might only come to the attention of services when they are arrested for possession of drugs, or excluded from school for their behaviour. Even then, questions are not always asked about why they are in this situation and they are treated as criminals and not offered help.

For girls who are criminally exploited, it may be even easier to fall through the gaps. There is not enough awareness among parents, professionals and in the community that girls may be exploited by criminal groups through county lines operations.

Any child can become a victim of exploitation, though Counting Lives shows that a combination of factors can put children at higher risk:

• Their vulnerability as a child, which can be exacerbated if they have additional needs like learning difficulties.

• Vulnerability created by society - for example poverty, experiences of discrimination, lack of opportunities, or the inability to access education.

• The lack of protective factors in a child’s life, including a lack of support from their family or the local community.

• The proximity or access a perpetrator has to a child.

COVID-19 can exacerbate many of these factors in the lives of children increasing the risk of them being targeted by criminals.

Exploitation never stops. Even during the current pandemic, when children and families have been forced to spend more time in their homes, there are concerns that exploitation has continued. Many vulnerable children have been at even more risk. Being away from school and spending more time at home has meant they have been ‘invisible’ to professionals who might have helped them, such as teachers in schools or youth workers. There are also concerns that more are being groomed for exploitation through online platforms as children are relying more on technology to stay in touch with friends and family, and to learn.

That’s why it is so important, now more than ever, that children are supported and protected. We all have a role to play in keeping children safe. As criminals are targeting, and trapping children in exploitative situations, it is the responsibility of professionals and everyone in children’s lives, as well as wider communities, to do everything they can to prevent and disrupt exploitation and protect children.

At The Children’s Society we work with children and families affected to help children stay safe. We also raise awareness among professionals and decision-makers of signs of exploitation and steps that need to be taken to disrupt it.

To help prevent criminal exploitation from happening, we need changes to the law to make coercion and control of children for the purpose of exploitation a criminal offence. We need to change systems that make children vulnerable, address poverty and provide the support they need.

Yet, the first step to making things better is something that does not require any policy changes. It is about showing young people that we care, that they can trust us and that we are there to support them to stay safe. Each of us needs to be more like the train conductor who our heroine meets in this play - kind, non-judgemental, caring and able to act on signs that a child is at risk.

For resources on how to identify the signs of criminal exploitation and what to do if you are worried a child may be being exploited, please visit www.childrenssociety.org.uk/what-we-do/our-work/tackling-criminal-exploitation-and-county-lines/county-lines-resources

For many of us, the Coronavirus pandemic has brought problems in our lives into sharp focus. For girls and young women already feeling cut off or overlooked, this period has magnified the challenges they face.

‘Social distancing’ has explicitly asked us to keep apart. To avoid one another, not to gather together, form large groups or go to the kind of places that provide us with social support and contact.

For many of the girls and young women Agenda hears from, the challenges they have faced growing up – domestic abuse, mental health problems, poverty - can already leave them feeling isolated, abandoned, and not knowing where to turn for the help they need.

Early experiences of being hurt or let down by family, excluded from school or repeatedly moved between care placements, can be deeply unsettling. Sometimes, when help or interventions do come, these can lead to them feeling further disconnected from the lives they knew. Even when the environment they were living in before was tough, being torn out of it can be even harder, as Sheena told us:

"All my friends are in [my city]… like as much as like I didn’t get along with my family and whatever else, all my friends, everything I knew - I know every street in [my city], I know how to get [every]where."

Children facing greater disadvantage and poverty report feeling lonelier than others; 27.5% of children aged 10 to 15 who received free school meals said they were “often” lonely, compared with 5.5% of those who did not. And as they get older, girls report loneliness at higher rates than boys. Only a third of young women aged 16 to 24 say that they “hardly ever or never” felt lonely, compared with nearly half of young men.

Feelings of loneliness are likely to be exacerbated for young women with other marginalised identities, including LGBTQ girls or Black, Asian and ethnic minority young women, for whom loneliness may also be associated with experiences of discrimination. In the context of events such as the tragic deaths of George Floyd and Belly Mujinga, and subsequent Black Lives Matter protests, it is likely that reminders of the grave inequalities some groups of minoritised young women face could leave them feeling particularly isolated.

There can be stigma or embarrassment associated with admitting to feeling lonely. For young women already facing social stigma – perhaps relating to being a young mum, being in trouble with the police or experiencing problems at home – the shame they might feel may stop them from describing how they really feel.

Being hurt or having their trust betrayed by those meant to love them - like family or intimate partners - can leave young women traumatised and have a profound impact on their ability to trust others. Which is why – when young women need help - being able to develop positive trusting relationships with adults and peers is critical. And why having had limited access to that kind of support during lockdown has been even harder for some.

Rebecca, who was exploited as a teenager by people she thought of as her friends, told us about the importance of being able to get support from a specialist young women’s service, and how vital this was to combating her isolation.

"I’m 26 now but I still need support. I’ve got no family support and no friends really, so the support workers here are the only support I’ve got."

The government recognises loneliness as a condition that should and can be challenged. This acknowledges some of the ways in which women might be affected – as carers, if they face language barriers, or if they’re in prison and separated from family. But this doesn’t go far enough to understand the specific challenges younger women might face.

Too little attention is given to the reality of young women’s lives, particularly for girls who are most marginalised and too quickly overlooked. Which is why Agenda has launched Girls Speak to hear more from young women and the services supporting them, to help develop a better understanding of the challenges girls face and find solutions to improve their lives.